Anti-fibrinolytic agents are commonly used for the treatment or prevention of bleeding. Three formulas of anti-fibrinolytic drugs are in use: aprotinin, tranexamic acid (TXA) and epsilon aminocaproic acid (EACA). TXA (Cyklokapron®) is about eight times more potent than its analogue EACA. Aprotinin proved effective at reducing blood transfusions in cardiac surgery, but due to concerns about serious adverse events it was withdrawn from the market in 2007 (1). The most studied anti-fibrinolytic drug for a variety of surgical and medical indications is TXA.

Mechanism of Action

TXA is a synthetic lysine analogue, that binds to lysine-binding sites of plasminogen. This prevents the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, thereby reducing fibrinolysis, and stabilizing the fibrin-rich clot.

Evidence-based Indications

1. Trauma

The landmark CRASH-2 (Clinical Randomization of an Antifibrinolytic in Significant Hemorrhage) trial enrolled 20,211 adult trauma patients with or at risk of significant bleeding and randomized them to TXA (1g over 10 minutes then 1g infusion over 8 hours) or placebo. (1) The TXA group had significantly reduced all-cause mortality compared to placebo (14.5% vs. 16.0%; RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.85-0.97; p=0.0035) and significantly reduced risk of death due to bleeding (4.9% vs. 5.7%; RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.76-0.96; p=0.0077). There was no significant difference in vaso-occlusive events between groups. A subgroup analysis showed that TXA had the greatest benefit when given within 3 hours of injury.

The CRASH-3 trial enrolled 12,737 patients with traumatic brain injury (TBI) to receive TXA (1g IV then 1g infusion over 8 hours) or placebo. (2) In patients treated within 3 hours of injury, TXA showed a trend toward reduced risk of head injury-related death (18.5% vs. 19.5%, RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.86-1.02). The risk of head injury related death was reduced with TXA in patients with mild to moderate head injury, but not in patients with severe head injury. Rates of vaso-occlusive events and seizures were similar between groups.

Conclusion: TXA safely reduces mortality in bleeding trauma patients and patients with TBI and should be given as early as possible (within 3 hours of injury) for the greatest benefit.

2. Cardiac surgery

The ATACAS (Aspirin and Tranexamic Acid for Coronary Artery surgery) trial randomized 4,631 patients undergoing coronary artery surgery and were at risk of perioperative complications to receive TXA (100mg/kg) or placebo.(3) The dose was changed mid-way through the study to 50mg/kg due to increased reports of seizures thought to be dose-related. The primary outcome, a composite of death and thrombotic complications, occurred in 16.7% in the TXA group and 18.1% in the placebo group (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.05; p=0.22). There was less major bleeding or cardiac tamponade leading to re-operation in the TXA group (1.4% vs. 2.8%) and significantly fewer number of red blood cell transfusions.

The ATACAS trial highlighted that in patients undergoing coronary artery surgery, there is increased postoperative seizure with TXA however, it was not powered to evaluate dose-dependency. The OPTIMAL (Outcome Impact of Difference Tranexamic Acid Regimes in Cardiac Surgery with Cardiopulmonary Bypass) trial comparing high-dose vs low-dose TXA found a non-significant higher seizure risk in the high-dose TXA group (1.0% vs. 0.4%; 95% CI 0.0-1.2, p=0.05). (4) However, a meta-analysis of TXA trials showed there is a dose-dependent increase in risk of seizure, with increased risk in patients receiving >2g/day. (5,6)

Conclusion: In patients undergoing coronary-artery surgery, TXA was associated with a lower risk of bleeding compared to placebo, and no increased risk of death or thrombotic complications. However, high-dose TXA (e.g. 100 mg/kg) was associated with a higher risk of postoperative seizures.

3. Non-cardiac surgery

The POISE-3 (Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation-3) trial included 9,535 patients undergoing non-cardiac surgery who were randomized to TXA (1g IV bolus) or placebo.(7) The primary efficacy outcome was a composite of life-threatening bleeding, major bleeding, or bleeding into a critical organ at 30 days and occurred 9.1% in the TXA group and 11.7% in the placebo group (HR 0.76; 95% CI 0.67-0.87; p<0.001). The primary safety outcome (a composite of myocardial injury after noncardiac surgery, nonhemorrhagic stroke, peripheral arterial thrombosis, or proximal venous thromboembolism) occurred in 14.2% in the TXA group and 13.9% in the placebo group (HR 1.02; 95% CI 0.92-1.14). This did not meet the criterion for non-inferiority (p=0.04 for non-inferiority). There was no significant difference in postoperative seizure (0.2% vs. 0.1%, HR 3.35, 95% CI 0.92-12.20), although patients with a history of seizure were excluded from POISE-3.

Conclusion: In non-cardiac surgery, TXA significantly reduced major bleeding. However, TXA did not clearly meet non-inferiority criteria for the composite cardiovascular outcome.

4. Orthopedic surgery

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 29 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) in total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty found that antifibrinolytics (TXA was used in 65.5% of patients) significantly reduced blood loss and transfusion requirements, with no increase in venous thromboembolism. (8) Various routes of TXA administration (topical, intraarticular, or IV) has been studied in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty and other orthopedic surgeries and have shown similar efficacy and safety. (9,10) In spinal surgery, a meta-analysis of 13 studies found that TXA is effective in reducing intraoperative blood loss without increasing the risk of complications. (11) Lastly, the POISE-3 trial described above included patients undergoing orthopedic surgery and showed TXA safely reduced bleeding outcomes. (7)

Conclusion: TXA reduces perioperative blood loss and the need for RBC transfusion in orthopedic surgery, without increased thrombotic risk.

5. Postpartum bleeding

Treatment of postpartum bleeding

The WOMAN (World Maternal Antifibrinolytic) trial randomized 20,060 women with postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) after vaginal delivery or cesarean section to TXA (1 g IV) or placebo. Death due to bleeding was significantly reduced in patients who received TXA (1.5% vs. 1.9%, RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.65-1.00, p=0.045), especially when given within 3 hours of birth. However, TXA did not reduce the composite primary end point of death from all causes or hysterectomy (5.3% vs. 5.5%, RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.87-1.09, p=0.65). There was no significant difference between groups in thromboembolic events or seizure.

Prevention of postpartum bleeding

Several studies have investigated TXA for the prevention of PPH. In patients undergoing vaginal delivery, the TRAAP (Tranexamic acid for Preventing Postpartum Hemorrhage Following a Vaginal Delivery) trial found that prophylactic TXA (1 g IV) plus uterotonics did not significantly reduce PPH (≥500 mL) compared to uterotonics alone. (12)

In patients undergoing cesarian section, the TRAAP-2 trial found that prophylactic TXA plus uterotonics significantly reduced PPH (defined as estimated blood loss >1000mL or receipt of red cell transfusion) compared to uterotonics alone (26.7% vs. 31.6%). (13) In both TRAAP and TRAAP-2 studies, there was a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting in the TXA group. A subsequent trial designed to evaluate whether prophylactic TXA reduced maternal death or blood transfusion found that TXA did not reduce these outcomes (3.5% vs. 4.6%, p=0.19). (14)

Pregnant patients with anemia are at higher risk of PPH. Thus, the WOMAN-2 trial investigated prophylactic TXA (1g TXA IV within 15 minutes of umbilical cord clamping) compared to placebo in women in active labor with moderate to severe anemia (hemoglobin <100g/L) and found that that TXA did not reduce the risk of clinically diagnosed PPH (7.0% vs. 6.6%, RR 1.05, 95% CI 0.94-1.19). (15) In all trials, there was no increase in thromboembolic events with TXA.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of five RCTs including WOMAN, WOMAN-2, TRAAP, and TRAAP-2 trials found that TXA reduced life-threatening bleeding compared to placebo (0.65% vs. 0.85%, OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63-0.93) with no significant difference in odds of thrombosis. (16)

Conclusion: TXA safely reduces mortality from bleeding in women diagnosed with PPH and should be given as early as possible (within 3 hours) after birth. Prophylactic TXA may be considered in women at high risk of severe PPH, although routine use has not shown a reduction in maternal mortality or transfusion.

6. Heavy menstrual bleeding

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is defined as menstrual blood loss (MBL) >80mL per cycle or that interferes with physical, emotional, and social quality of life.(17) An RCT in adults with HMB compared TXA 3.9 g/d (for the first 5 days of each cycle, over 6 cycles) to placebo. (18) Women in the TXA group had significantly greater reduction in MBL compared to placebo (-69.6mL vs. -12.6mL, p<0.001). TXA also improved health related quality of life. TXA was well tolerated, with mild to moderate gastrointestinal side effects reported. (18) A Cochrane systematic review of 13 RCTs confirmed that TXA is effective for treating HMB compared to placebo, NSAIDs, oral luteal progestogens, ethamsylate, or herbal remedies, but may be less effective than the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. (19)

Conclusion: TXA reduces menstrual blood loss and improves quality of life in women with heavy menstrual bleeding.

7. Von Willebrand Disease

TXA should be used for the prevention and treatment of bleeding in patients with von Willebrand disease (VWD). Specific recommendations for the use of TXA in the ASH ISTH NHF WFH 2021 guidelines on the management of VWD include (20):

- Minor surgeries or procedures: Raise VWF activity to >0.50 IU/mL with desmopressin or VWF concentrate, plus TXA.

- Type 1 VWD (baseline VWF >0.30 IU/mL) & mild bleeding, minor mucosal procedures: TXA alone.

- Women with VWD and HMB who do not wish to conceive: Hormonal therapy (combined hormonal contraceptive or levonorgestrel intrauterine system) or TXA.

- Women with VWD and HMB who wish to conceive: TXA.

- Postpartum women with type 1 VWD: TXA 25 mg/kg (typically 1 g) by mouth three times daily for 10-14 days (or longer if bleeding remains heavy).

TXA has not shown benefit in the following patient populations

Gastrointestinal bleeding: The HALT-IT trial found that in patients with acute upper or lower gastrointestinal bleeding, TXA did not reduce death due to bleeding (4.0% vs. 4.0%; RR 0.99; 95% CI 0.82-1.18) (21) In fact there was evidence of harm; patients that received TXA had higher rates of venous thrombosis (0.8% vs. 0.4%; RR 1.85; 95% CT 1.15-2.98) and seizure (0.6% vs. 0.4%; RR 1.73; 95% CI 1.03-2.93). (21)

Hematologic malignancies: The A-TREAT (American Trial Using Tranexamic Acid in Thrombocytopenia) trial found that in patients undergoing treatment for hematologic malignancies, prophylactic TXA compared to placebo did not significantly reduce the risk of WHO grade >2 bleeding. (22)

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage (increased risk of cerebral ischemia) (25)

- Hypersensitivity to TXA

- Active thromboembolic disease

In Canada, the product monograph also lists the following contraindications:

- Disturbances of color vision

- Hematuria (risk of urinary tract clots and obstruction). However, available evidence does not indicate an increased risk of renal failure in TXA-treated patients with hematuria. (26)

Dosing

TXA is indicated for oral or intravenous use only. Intrathecal and epidural administration of TXA has caused serious harm, including death. (27)

Intravenous TXA:

- Ampoule sizes: 5 mL, 10 mL

- Concentration: 100 mg/mL (1 g = one 10 mL vial or two 5 mL vials)

- Typical adult dose: 1 g IV bolus over at least 5 minutes, then 1 g IV over 8 hours (infusion)

Oral TXA:

- Tablet strength: 500 mg

- Typical adult dose: 1,000–1,500 mg by mouth every 8-12 hours

- Pediatric dose: 25 mg/kg by mouth every 8-12 hours

As the main route of elimination of TXA is via the urine, dose adjustment is required for renal impairment per the following:

| Serum creatinine | Recommended ORAL dose | Recommended IV dose |

| 120-250 umol/L | 15 mg/kg twice daily | 10 mg/kg twice daily |

| 250-500 umol/L | 15 mg/kg daily | 10 mg/kg daily |

| >500 umol/L | 15 mg/kg every 2 days | 10 mg/kg every 2 days |

Adverse events

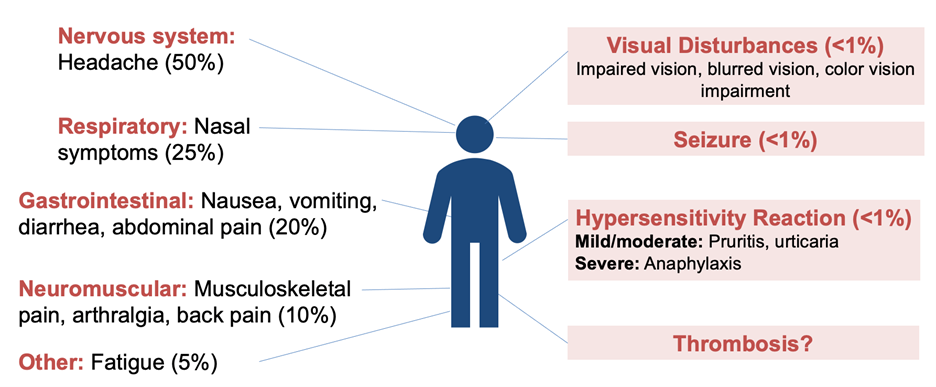

TXA is generally well tolerated. Common side effects include mild gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. nausea, diarrhea) and rarely hypotension with rapid IV injection. TXA has not been associated with an increased risk of thromboembolism in most trials. The most serious adverse effect is seizure, mainly reported at higher doses or in cardiac surgery patients.

References

1. Shakur H, Roberts I, et al. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, vascular occlusive events, and blood transfusion in trauma patients with significant haemorrhage (CRASH-2): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. Jul 3 2010; 376(9734):23–32. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60835-5

2. CRASH-3 collaborators. Effects of tranexamic acid on death, disability, vascular occlusive events and other morbidities in patients with acute traumatic brain injury (CRASH-3): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. Nov 9 2019; 394(10210):1713–1723. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32233-0

3. Myles PS, Smith JA, Forbes A, et al. Tranexamic Acid in Patients Undergoing Coronary-Artery Surgery. The New England journal of medicine. Jan 12 2017; 376(2):136–148. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1606424

4. Williamson DR, Lesur O, Tetrault JP, Nault V, Pilon D. Thrombocytopenia in the critically ill: prevalence, incidence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes. Can J Anaesth. Jul 2013; 60(7):641–51. doi:10.1007/s12630-013-9933-7

5. Lin Z, Xiaoyi Z. Tranexamic acid-associated seizures: A meta-analysis. Seizure. Mar 2016; 36:70–73. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2016.02.011

6. Murao S, Nakata H, Roberts I, Yamakawa K. Effect of tranexamic acid on thrombotic events and seizures in bleeding patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. Nov 1 2021;25(1):380. doi:10.1186/s13054-021-03799-9

7. Devereaux PJ, Marcucci M, Painter TW, et al. Tranexamic Acid in Patients Undergoing Noncardiac Surgery. The New England journal of medicine. May 26 2022; 386(21):1986–1997. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2201171

8. Kagoma YK, Crowther MA, Douketis J, Bhandari M, Eikelboom J, Lim W. Use of antifibrinolytic therapy to reduce transfusion in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery: a systematic review of randomized trials. Thromb Res. Mar 2009;123(5):687–96. doi:10.1016/j.thromres.2008.09.015

9. Goyal N, Chen DB, Harris IA, Rowden NJ, Kirsh G, MacDessi SJ. Intravenous vs Intra-Articular Tranexamic Acid in Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Randomized, Double-Blind Trial. J Arthroplasty. Jan 2017; 32(1):28–32. doi:10.1016/j.arth.2016.07.004

10. Montroy J, Hutton B, Moodley P, et al. The efficacy and safety of topical tranexamic acid: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Transfus Med Rev. Feb 19 2018;doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2018.02.003

11. Yamanouchi K, Funao H, Fujita N, Ebata S, Yagi M. Safety and Efficacy of Tranexamic Acid in Spinal Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Spine Surg Relat Res. May 27 2024;8(3):253–266. doi:10.22603/ssrr.2023-0244

12. Sentilhes L, Winer N, Azria E, et al. Tranexamic Acid for the Prevention of Blood Loss after Vaginal Delivery. The New England journal of medicine. Aug 23 2018;379(8):731–742. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1800942

13. Sentilhes L, Deneux-Tharaux C. Tranexamic Acid for the Prevention of Blood Loss after Cesarean Delivery. Reply. The New England journal of medicine. Aug 5 2021;385(6):575. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2109676

14. Pacheco LD, Clifton RG, Saade GR, et al. Tranexamic Acid to Prevent Obstetrical Hemorrhage after Cesarean Delivery. The New England journal of medicine. Apr 13 2023;388(15):1365–1375. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2207419

15. WOMAN-2 Trial Collaborators. The effect of tranexamic acid on postpartum bleeding in women with moderate and severe anaemia (WOMAN-2): an international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. Oct 26 2024;404(10463):1645–1656. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01749-5

16. Ker K, Sentilhes L, Shakur-Still H, et al. Tranexamic acid for postpartum bleeding: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. Oct 26 2024;404(10463):1657–1667. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(24)02102-0

17. Health NCCfWsaCs. Heavy Menstrual Bleeding. 2007.

18. Lukes AS, Moore KA, Muse KN, et al. Tranexamic acid treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. Oct 2010;116(4):865–875. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181f20177

19. Bryant-Smith AC, Lethaby A, Farquhar C, Hickey M. Antifibrinolytics for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Apr 15 2018;4(4):CD000249. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000249.pub2

20. Connell NT, Flood VH, Brignardello-Petersen R, et al. ASH ISTH NHF WFH 2021 guidelines on the management of von Willebrand disease. Blood Adv. Jan 12 2021;5(1):301–325. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003264

21. Collaborators H-IT. Effects of a high-dose 24-h infusion of tranexamic acid on death and thromboembolic events in patients with acute gastrointestinal bleeding (HALT-IT): an international randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. Jun 20 2020;395(10241):1927–1936. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30848-5

22. Gernsheimer TB, Brown SP, Triulzi DJ, et al. Prophylactic tranexamic acid in patients with hematologic malignancy: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. Blood. Sep 15 2022;140(11):1254–1262. doi:10.1182/blood.2022016308

23. Pfizer. CYKLOKAPRON. 2024.

24. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Cyklokapron (tranexamic acid) – Prescribing Information.

25. Baharoglu MI, Germans MR, Rinkel GJ, et al. Antifibrinolytic therapy for aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Aug 30 2013;2013(8):CD001245. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001245.pub2

26. Lee SG, Fralick J, Wallis CJD, Boctor M, Sholzberg M, Fralick M. Systematic review of hematuria and acute renal failure with tranexamic acid. Eur J Haematol. Jun 2022; 108(6):510–517. doi:10.1111/ejh.13762

27. Canada IfSMP. Alert: Substitution Error with Tranexamic Acid during Spinal Anesthesia. 2022.

28. Relke N, Chornenki NLJ, Sholzberg M. Tranexamic acid evidence and controversies: An illustrated review. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. Jul 2021;5(5):e12546. doi:10.1002/rth2.12546

The authors

Original version created by Sima Zolfaghari and Marian van Kraaij. Current version revised by Sima Zolfaghari and Nicole Relke.

Click the below link to go back to the Patient Blood Management Resources Homepage.