Sickle cell disease (SCD) and ß thalassemia are complex hemoglobinopathies. Although they are grouped together here, their clinical manifestations and treatment modalities differ significantly.

Homozygeous ß Thalassemia can be categorized into two clinical groups:

- “Transfusion-dependent thalassemia, TDT”: These patients require regular transfusions starting from infancy to sustain life and suppress ineffective erythropoiesis

- “Non-transfusion dependent thalassemia, NTDT”: These patients typically have moderate hemolytic anemia but maintaining hemoglobin (Hb) levels sufficient for normal growth and development without transfusion support. (1) However, patients with NTDT may experience worsening anemia in response to physiological stress, such as pregnancy or infections, or other triggers necessitating intermittent transfusion support. (2)

This guideline provides a summary of current evidence on transfusion practices for SCD and thalassemia. It is not exhaustive and should not replace clinical judgment. It is intended to serve as a general guide. Decisions must be tailored to the individual patient, and may require consultation with a hematologist experienced in managing SCD and thalassemia. Please refer to the cited guidelines for specific recommendations.

Blood Banking and Transfusion Recommendations

- Perform an extended RBC phenotype or genotype for all patients with SCD (all genotypes) and ß thalassemia at the earliest possibility (optimally before the first transfusion). (3, 4) This ideally should be performed in the first year of life before the start of a regular transfusion program. (5, 6)

- For SCD patients, baseline extended phenotype/genotype should include C/c, E/e, K, Jka/Jkb, Fya/ Fyb, M/N, S/s at a minimum. (3)

- For ß thalassemia patients, baseline extended RBC phenotype/genotype should be at least for Rh C/c, D, E/e and Kell, and if available a full red cell pheno/genotype. (4)

- If the patient has been recently transfused, DNA-based methods can be used to determine the predicted phenotype. (7) The ASH guidelines recommend genotype over serologic phenotyping, as it provides additional antigen information and increased accuracy for C antigen determination and Fyb antigen matching. (3)

- A full cross-match and antibody screen of new antibodies should be performed before each transfusion. In centers that meet regulatory requirements, an electronic cross match can be performed.

- Every patient should have a complete record of red cell phenotype, antibodies, and transfusion reactions..

- At each transfusion, ABO, Rh(D) compatible blood should be given.

- ASH guideline panel recommends prophylactic red cell antigen matching for Rh (C, E or C/c, E/e) and K antigens over only ABO/RhD matching for patients with SCD (all genotypes) receiving transfusions. This May be determined by serology or genotype-predicted profile (3).

- For patients with SCD who do not have any known alloantibodies and who are anticipated to have a transfusion (either top-up/small volume or exchange) should probably be transfused with ABO, RhD, RhCcEe, and K- matched RBCs to reduce the risk of alloimmunisation and delayed haemolytic transfusion reactions (HTRs). (8)

- Patients with thalassaemia who do not have any known alloantibody(ies) should be transfused with ABO, RhD, RhCcEe, and K-matched RBCs to reduce the risk of alloimmunisation and delayed HTRs. (4, 8)

- Patients with SCD or thalassemia, who have one or more clinically significant alloantibody(ies), should be transfused with RBCs negative for the corresponding antigen(s) and cross match compatible. (8)

- Due to the lack of evidence to support extended prophylactic matching, and the uncertain impact on the resources, the existing guidelines could not make a recommendation as to whether patients with SCD or thalassemia, who have one or more alloantibodies, should be transfused with more extensive antigen-matched RBCs (i.e. RhCcEe, K, Fya, Fyb, Jka, Jkb, S, s–matched) to reduce the risk of further alloimmunisation. (8)

- Red cell antigen and antibody profiles should be made available across hospital systems. (3) This facilitates transfusion support for patients who present at different hospitals.

- RBC units for patients with SCD should be sickle test negative. (9)

- It is recommended to provide fresh units (less than 10-14 days old) if possible, for SCD and thalassemia patients, as fresher units may reduce frequency of transfusion. (5, 9, 10) Fresher units can be chosen over older units. (4, 10)

- Leukoreduced packed red cells (reduction to 1x106/L or less), preferably through pre-storage filtration, are recommended. Bedside filtration is only acceptable if there is no capacity for pre-storage filtration or blood bank pretransfusion filtration. (4, 10)

- Washed red blood cells should be used for patients who have severe allergic reaction and those who have IgA deficiency with antibodies.(4, 10)

- Cytomegalovirus negative components are recommended for potential candidates for stem cell transplantation. (1)

- Chronic transfusion can cause iron overload and related cardiac, hepatic, and endocrine complications, hence monitoring and chelation therapy are necessary.

- Before first transfusion, a course of hepatitis B vaccination should be started and completed if possible. (5) Minimum mandatory serologic testing for antibodies to HCV, HIV-1 and HIV-2, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) assay, and treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay (TPHA) should be performed as baseline measures (4, 10). Additional serological screening tests for blood donors may be required by national authorities.

- All patients who are seronegative for hepatitis B virus (ie do not have serologic immunity to hepatitis B) should start a vaccination program and show evidence of immunity before the start of the transfusion. (6, 9, 11) Vaccinated patients should be tested annually for anti-HBs, and a booster dose of the HBV vaccine should be considered if the anti-HBs titre decreases. (4, 10)

Transfusion indications in Sickle Cell Disease

Indications for acute Transfusion

- Acute ischemic stroke: Transfusion has been shown to be beneficial in the management of ischemic stroke. Urgent transfusion is required in patients with acute neurological symptoms, including transient ischemic attacks, preferably within 2 hours of acute neurological symptom presentation. (9, 12, 13) The type of transfusion (simple, exchange) is dependent on individual patient factors and local transfusion resources. The ASH guidelines suggest exchange transfusion over simple transfusion,(13) targeting HbS < 15-20%. If the Hb level is ≤ 8.5 g/dl, the ASH guidelines recommend increasing the Hb to 10.0 g/dL with a simple transfusion, within 2 hours after presentation to medical care, followed by automated-exchange red blood cell transfusion. (9, 13) In cases receiving simple transfusion, it is important to avoid hypervolemia during the procedure and to keep the post transfusion Hb at 10 g/dl then follow with exchange transfusion, as a high hematocrit may worsen the neurological insult. (9, 12)

- Transient aplastic crisis and acute anemia: Simple transfusions may be necessary especially if the acute anemia is accompanied with reticulo-cytopenia suggestive of parvovirus B19 infection,(14) in symptomatic patients, or in those who show signs of imminent or established cardiovascular compromise. The threshold Hb level for the transfusion depends on the patient’s baseline Hb and clinical status, while the target is the patient’s Hb steady-state level. (9) Exchange transfusion is indicated in the unwell patient with exacerbation of the anemia due to acute multi-organ failure.(12, 15)

- Splenic and hepatic sequestration: In patients with splenic and hepatic sequestration, simple or exchange transfusion is recommended based on expert consensus.(14) However, transfusion should be managed cautiously with small volumes to avoid hyper-viscosity due to the return of the sequestered RBC to the circulation. Over-transfusion to Hb > 8 g/dl should be avoided. Patients with recurrent episodes of splenic sequestration (two or more) should be considered for splenectomy.(12)

- Acute chest syndrome (ACS): If there is suspicion of ACS, it is advisable to ensure availability of blood for exchange transfusion ahead of time, as acute respiratory failure can intervene rapidly, and blood transfusion can be lifesaving. Transfusion may be given by simple or exchange depending on the clinical severity. (12) The ASH guideline suggests automated red cell exchange or manual red cell exchange over simple transfusions in patients with SCD and moderate or severe ACS.(3) Although there are no specific markers of disease severity, a significant decline in the Hb and/or oxygen saturations (SpO2 < 94% or several percentage points below the patient’s baseline) can suggest severe disease. Exchange transfusion is also recommended in patients who fail to response to simple transfusion, or patients with a higher Hb level (> 90 g/dl) at time of presentation. (3, 12, 16) Early top-up simple transfusion may avoid the need for exchange transfusion in these patients. (9) A target HbS of < 30-40% is often used, but should be guided by the clinical response. (16)

- Complicated vaso-occlusive crisis/Severe SCD crisis: Transfusion is beneficial in selected patients with severe SCD crisis with significant Hb drop, hemodynamic compromise or concern of impending critical organ complications. (12)

- Acute Priapism: The benefit of transfusion to relieve acute priapism has not been evaluated in RCTs. (12) Therefore, transfusion is not recommended for patients with acute priapism.(14) However, patients may benefit from exchange transfusion if no response to a shunt or drainage procedure. (12, 17)

- Acute multisystem failure: An exchange or simple transfusion may be useful in such cases, including in cases with severe sepsis. (12, 14, 18)

There are no data at present to support transfusion in the acute management of hemorrhagic stroke. There is insufficient evidence for the benefit of blood transfusion for managing leg ulcers, avascular necrosis, pulmonary hypertension, end-stage liver disease and progressive sickle cell retinopathy. A full risk assessment is recommended with consultation with an experienced hematologist. (12, 14)

Indications for chronic transfusion, Primary stroke prevention and silent cerebral infarcts

The best data to support chronic transfusion in SCD patients are for primary infarctive stroke prevention (19, 20) and secondary prevention of silent cerebral infarcts in pediatric patients. (21) The below recommendations are tailored to SCD children (HbSS or HbSB0) aged 2-16 years.

- Annual Transcranial Doppler (TCD) ultrasound assessment in SCD with HbSS or HbSβ0 thalassemia children from the age of 2 years is recommended. (13)

- Children with SCD with raised cerebral blood flow-velocities ≥ 200 cm/s benefit from a chronic transfusion program aiming to maintain HbS < 30%.(9, 12, 13, 19)

- Regular transfusion should be continued throughout childhood (up to the age 16 years), as a significant number of children revert to high TCD velocities or develop overt stroke after discontinuation.(12, 20)

- Hydroxyurea can be considered for primary stroke prevention in children with SCD and abnormal TCD screening if living in low-middle-income countries where regular blood transfusion and chelation therapy are not available or affordable. (13)

- Hydroxyurea can be considered at the maximum tolerated dose after a minimum of one year of initial transfusion in children with SCD and abnormal TCD results with no severe Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA)-defined cerebral vasculopathy or prior silent cerebral infarcts.(12, 13, 22) For patients with MRA-defined vasculopathy or silent cerebral infarcts, it is recommended to continue regular blood transfusions indefinitely. (12, 13)

- Blood transfusion was found to reduce the incidence of infarct recurrence in children with SCD and silent cerebral infarcts.(21) Long term transfusion (aiming Hb > 9 g/dl and HbS < 30% until the time of the next transfusion) should be offered to children who are identified as being at the greatest risk for secondary stroke prevention. (12, 21)

- TCD has not been validated in adults SCD patients, and there are no studies performed to evaluate the efficacy of transfusion for primary stroke prevention in this group of patients, nor in patients who have been on long-term transfusions for primary stroke prevention since childhood.(12) Management of these patients should be decided individually.

Indications for chronic transfusion, secondary stroke prevention

- Transfusion plus chelation is superior to hydroxyurea for secondary stroke prevention in children with SCD.(23) Long-term transfusion is recommended for children with SCD (HbSS or HbSB0) to aiming at Hb > 9 g/dl at all times and maintaining HbS level at <30% until the time of the next transfusion. (24)

- Transfusion for secondary stroke prevention my need to be continued indefinitely, but should also be tailored to the needs of the patients and get reviewed regularly with the patient &/or parents.(12)

- For children who cannot be transfused or refuse transfusion, hydroxyurea therapy is an inferior alternative to regular blood transfusion for secondary stroke prevention, but superior to no therapy at all.(13)

- Adolescents who had a stroke as a child should continue transfusion into adulthood for secondary stroke prevention.(13)

- Data on transfusion for secondary stroke prevention in adult SCD patients is limited. Long-term transfusion to maintain HbS <30% is however recommended for the prevention of recurrent stroke. (12)

Pregnancy

- There is insufficient evidence to recommend a strategy of prophylactic transfusion rather than standard of care in SCD.

- Considering that hydroxyurea has been demonstrated to be teratogenic in animal models in high doses, the most commonly used strategy during pregnancy is scheduled red cell transfusion. However, the benefit to the fetus and the mother are unclear.

- Existing guidelines suggests either prophylactic transfusion at regular intervals or standard care (transfusion when clinically indicated for a complication or Hb lower than baseline) for pregnant patients with SCD (all genotypes).(24)

- Prophylactic transfusion should be considered in patients with previous or current medical, obstetric or fetal complications related to SCD, additional comorbidities of high-risk pregnancies, patients with multiple pregnancies, women who develop SCD-related complications during the current pregnancy and patients previously on hydroxyurea because of severe disease.(12)

- Transfusion should be considered in women with worsening anemia or those with acute SCD complications (e.g acute chest syndrome, stroke).

- Routine prophylaxis is not routinely required and not recommended in uncomplicated pregnancies. (12, 25)

- Women on long term transfusion for other indications should continue regular transfusion throughout pregnancy.

Preoperative transfusion

- Existing guidelines suggest preoperative transfusion over no preoperative transfusion in patients with SCD undergoing surgeries requiring general anesthesia lasting >1 hour.(3)

- All other patients undergoing elective surgeries should be individually assessed, considering previous history, urgency and complexity of the surgery.

- Decision-making should be individualized based on genotype, the risk level of surgery, baseline Hb, complications with prior transfusions, and disease severity.

- Transfusions can be simple top up transfusions for patients with Hb <9 g/dl aiming for 11 g/dl before surgery, or via red cell exchange transfusion if the patient has a high baseline Hb (9-10 g/dL) & for patients undergoing very high-risk surgery (neurosurgery or cardiac surgery).

Recurrent/chronic painful crisis

- For adults and children with SCD and recurrent acute pain, existing guidelines suggest against chronic monthly transfusion therapy as a first-line strategy to prevent or reduce recurrent acute pain episodes.(26)

Other indications

- Other indications for long-term transfusion support in SCD are recurrent acute chest syndrome not prevented by hydroxyurea, or for whom it is contraindicated, recurrent vaso-occlusive crisis and progressive organ failure. (9, 12)

- Long-term transfusions may also benefit patients with recurrent painful crises, where hydroxyrea is ineffective or contraindicated.(12)

Transfusion Indications in homozygeous ß Thalassemia

Transfusion-dependent thalassemia (TDT)

- Once an infant with ß thalassemia is diagnosed, close monitoring from the age of 3 months is required for clinical signs necessitating the initiation of regular transfusion. The Hb level should be checked at least monthly.

- The decision of regular transfusion in infants with ß thalassemia usually occur in the first two years of life.(4, 10, 27)

- The decision for transfusion should consider the current clinical phenotype of the patient and anticipated short- and longer-term outcomes and should be taken in discussion with the patient or parents.

- Indication for initiation of regular transfusion in infants with ß thalassemia include severe anemia below 7 g/dl on two occasions >2 weeks apart in asymptomatic patient with a ß0 ß0 or ß0 ß+ or any other genotypes known to cause TDT and after excluding contributing causes such as infections. (4, 5, 10, 11, 27).

- Transfusion decision can be made based on clinical criteria irrespective of Hb level in patients exhibiting significant anemia symptoms, poor growth or failure to thrive, increasing splenomegaly, or complications from excessive intramedullary haematopoiesis-such as pathological fractures, bony expansions, and changes in facial bone appearance.(5, 27)

- This decision to initiate a long-term regular transfusion regimen should not only be driven by patient genotype or Hb level, or a transient drop in Hb due to an intercurrent infection.

- Reassessment after first transfusion is important to decide if regular transfusions are required or not. If the Hb falls again promptly, it is reasonable to assume longer term dependency necessitating the start of a regular transfusion program.(1, 5)

- Where possible, the decision for initiating regular transfusion should not be delayed until after the 3rd year of age, as the risk of alloimmunization increases in patients who are irregularly transfused or start transfusion later in life. (4, 5, 10)

- Regular transfusion should aim for a trough pre-transfusion Hb level of 9.5-10.5 g/dl.(4, 5, 10, 28) Occasional patients with cardiac disease, pulmonary hypertension, clinically significant extramedullary hematopoiesis &/or inadequate bone marrow suppression benefit from higher transfusion thresholds of 10-11 g/dl (or as high as practicable). (4, 5, 10)

- To achieve a pretransfusion Hb of 9.5-10.5 g/dl, aim for a post transfusion Hb of 13-15 g/dl.(4, 10)

- Post transfusion Hb should not be higher than 14-15 g/dl to avoid risk of hyper-viscosity and stroke.(27)

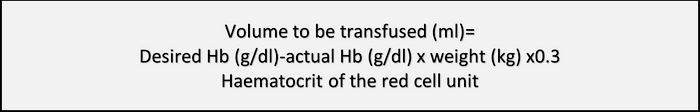

- For children or for others who may need specific volume (e.g those with underlying cardiac disease), volume to transfuse is calculated based on the below formula.(27, 29, 30)

- Once commenced, transfusions are usually given regularly every 2-4 weeks.(5) With aging patients, a transfusion every two weeks may be necessary. (11) Transfusion requirements are likely to increase in pregnant patients.

- It is recommended to maintain a record of transfusion including the volume or weight of administered units, the hematocrit of the units, the patient’s weight, transfusion reactions and red cell antibodies formed.(6, 27)

- In patients undergoing elective surgeries, a preoperative assessment should include transfusion history and baseline Hb levels to plan pre-and peri-operative transfusion regimen, and to allow surgeries to be undertaken with optimal Hb level.

- Splenectomy is sometimes indicated for hypersplenism and for those with splenectomy and high transfusion requirements.(31)

Non-Transfusion-dependent thalassemia (NTDT)

- It is important to monitor the patients once the diagnosis has been established to assess the transfusion requirements. Decision for transfusions depends on several factors rather than the Hb level alone. (32) Consider the increased risk of iron overload, endocrinopathies and alloimmunization when determining when to transfuse these patients. (33)

- For this group of patients, regular transfusions during childhood are generally unnecessary unless there is failure to thrive or noticeable bone changes. Therefore, in the first 3–5 years of life, children should be closely monitored for thalassemic signs caused by ineffective erythropoiesis. If needed, children may begin regular transfusions until they reach maximum height and their bones have fused, after which transfusions can be gradually reduced and eventually stopped. (5) It is essential to support good health and normal growth in the child while avoiding unnecessary transfusions in those presenting only minor symptoms.

- Older children, adolescents and adults should continue to be monitored regularly for any indications that may arise. Some adolescents will require transfusion because of poor growth, delayed/absent puberty, or complications due to bone expansions.

- In adults, transfusion may be needed for acute anemia, pregnancy, surgery, or infections. (2, 34, 35) It should also be considered for primary or secondary prevention in high-risk settings, such as thrombotic or cerebrovascular disease, pulmonary hypertension (with or without heart failure), extramedullary hematopoietic pseudo-tumors, leg ulcers, silent brain infarcts, and thrombotic events.(35) After starting transfusion, patients require close monitoring and individualized therapy. (35)

- The decision for regular transfusion should be made with consultation with a specialist in managing these patients. Indications include symptomatic anemia, delayed growth, bone deformities or fractures, pulmonary hypertension, chronic ankle ulceration , cerebrovascular accidents and silent ischemic lesions, and symptomatic extramedullary hematopoiesis. (5, 36)

References

1. Eliezer A, Patricia J. How I treat thalassemia. Blood. 2011

2. Taher A, Radwan A, Viprakasit V. When to consider transfusion therapy for patients with non‐transfusion‐dependent thalassaemia. Vox sanguinis. 2015

3. Chou ST, Alsawas M, Fasano RM, Field JJ, Hendrickson JE, Howard J, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: transfusion support. Blood Adv. 2020

4. Musallam KM, Cappellini MD, Porter JB, Farmakis D, Eleftheriou A, Angastiniotis M, et al. TIF Guidelines for the Management of Transfusion‐Dependent β‐Thalassemia. Hemasphere, 2025

5. Anne Yardumian PT, Farrukh Shah, Kate Ryan,Matthew W Darlison, Elaine Miller, George Constantinou. Standards for the Clinical Care of Children and Adults with Thalassaemia in the UK 3rd ed. London, UK: Thalassaemia Society; 2016.

6. Sayani F, Warner M, Wu J, Wong-Rieger D, Humphreys K, Odame I. Guidelines for the clinical care of patients with thalassemia in Canada. Anemia Institute for Research and Education & Thalassemia Foundation of Canada. 2009.

7. Veldhuisen B, van der Schoot CE, de Haas M. Blood group genotyping: from patient to high-throughput donor screening. Vox sanguinis. 2009

8. Wolf J, Blais‐Normandin I, Bathla A, Keshavarz H, Chou ST, Al‐Riyami AZ, et al. Red cell specifications for blood group matching in patients with haemoglobinopathies: An updated systematic review and clinical practice guideline from the International Collaboration for Transfusion Medicine Guidelines. British journal of haematology. 2025

9. Dick M. Sickle cell disease in childhood: standards and guidelines for clinical care. NHS Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Screening Programme; 2010.

10. Taher A, Farmakis D, Porter J, Cappellini M, Musallam K. Guidelines for the Management of Transfusion-Dependent β-Thalassaemia (TDT). TIF, 2025.

11. Vichinsky E, Levine L, Bhatia S, Bojanowski J, Coates T, Foote D, et al. Standards of care guidelines for thalassemia. Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland, USA. 2008.

12. Davis BA, Allard S, Qureshi A, Porter JB, Pancham S, Win N, et al. Guidelines on red cell transfusion in sickle cell disease Part II: indications for transfusion. British journal of haematology. 2016.

13. DeBaun MR, Jordan LC, King AA, Schatz J, Vichinsky E, Fox CK, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of cerebrovascular disease in children and adults. Blood Adv. 2020.

14. Linder GE, Chou ST. Red cell transfusion and alloimmunization in sickle cell disease. Haematologica. 2021.

15. Hassell KL, Eckman JR, Lane PA. Acute multiorgan failure syndrome: a potentially catastrophic complication of severe sickle cell pain episodes. The American journal of medicine. 1994.

16. Howard J, Hart N, Roberts‐Harewood M, Cummins M, Awogbade M, Davis B. Guideline on the management of acute chest syndrome in sickle cell disease. British journal of haematology. 2015.

17. Howard J, Malfroy M, Llewelyn C, Choo L, Hodge R, Johnson T, et al. The Transfusion Alternatives Preoperatively in Sickle Cell Disease (TAPS) study: a randomised, controlled, multicentre clinical trial. The Lancet. 2013.

18. Ohene-Frempong K. Indications for red cell transfusion in sickle cell disease. Seminars in hematology, 2001.

19. Adams RJ, McKie VC, Hsu L, Files B, Vichinsky E, Pegelow C, et al. Prevention of a first stroke by transfusions in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal results on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. The New England journal of medicine, 1998.

20. Adams RJ, Brambilla D. Discontinuing prophylactic transfusions used to prevent stroke in sickle cell disease. The New England journal of medicine. 2005.

21. DeBaun MR, Gordon M, McKinstry RC, Noetzel MJ, White DA, Sarnaik SA, et al. Controlled trial of transfusions for silent cerebral infarcts in sickle cell anemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2014.

22. Ware RE, Davis BR, Schultz WH, Brown RC, Aygun B, Sarnaik S, et al. Hydroxycarbamide versus chronic transfusion for maintenance of transcranial doppler flow velocities in children with sickle cell anaemia—TCD With Transfusions Changing to Hydroxyurea (TWiTCH): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet. 2016.

23. Ware RE, Helms RW. Stroke with transfusions changing to hydroxyurea (SWiTCH). Blood. 2012.

24. DeBaun MR. Initiating adjunct low-dose hydroxyurea therapy for stroke prevention in children with SCA during the COVID-19 pandemic. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2020.

25. Boga C, Ozdogu H. Pregnancy and sickle cell disease: A review of the current literature. Critical reviews in oncology/hematology. 2016.

26. Brandow AM, Carroll CP, Creary S, Edwards-Elliott R, Glassberg J, Hurley RW, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: management of acute and chronic pain. Blood Adv. 2020.

27. Cappellini M-D, Cohen A, Porter J, Taher A, Viprakasit V. Guidelines for the management of transfusion dependent thalassaemia (TDT). TIF publication. 2014.

28. Cazzola M, Borgna-Pignatti C, Locatelli F, Ponchio L, Beguin Y, De Stefano P. A moderate transfusion regimen may reduce iron loading in beta-thalassemia major without producing excessive expansion of erythropoiesis. Transfusion. 1997.

29. New HV, Berryman J, Bolton‐Maggs PH, Cantwell C, Chalmers EA, Davies T, et al. Guidelines on transfusion for fetuses, neonates and older children. British journal of haematology. 2016.

30. Davies P, Robertson S, Hegde S, Greenwood R, Massey E, Davis P. Calculating the required transfusion volume in children. Transfusion. 2007.

31. Rebulla P, Modell B. Transfusion requirements and effects in patients with thalassaemia major. The Lancet.1991.

32. Taher AT, Musallam KM, Cappellini MD, Weatherall DJ. Optimal management of β thalassaemia intermedia. British journal of haematology. 2011.

33. Taher AT, Musallam KM, Karimi M, El-Beshlawy A, Belhoul K, Daar S, et al. Overview on practices in thalassemia intermedia management aiming for lowering complication rates across a region of endemicity: the OPTIMAL CARE study. Blood. 2010;115(10):1886-92.

34. Haidar R, Mhaidli H, Taher AT. Paraspinal extramedullary hematopoiesis in patients with thalassemia intermedia. European Spine Journal. 2010.

35. Taher A, Vichinsky E, Musallam K, Cappellini M-D, Viprakasit V. Guidelines for the management of non transfusion dependent thalassaemia (NTDT). Thalassaemia International Federation, Nicosia, Cyprus; 2013.

36. Karimi M, Cohan N, De Sanctis V, Mallat NS, Taher A. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of Beta-thalassemia intermedia. Pediatric hematology and oncology. 2014.

The author

Original and current version created and revised by:

Click the below link to go back to the Patient Blood Management Resources Homepage.